February 15, 2018

My father would have been one hundred and three years old yesterday, had he not died of a heart-attack a foggy Halloween night seventeen years ago in the emergency room of a small hospital in southern New Jersey.

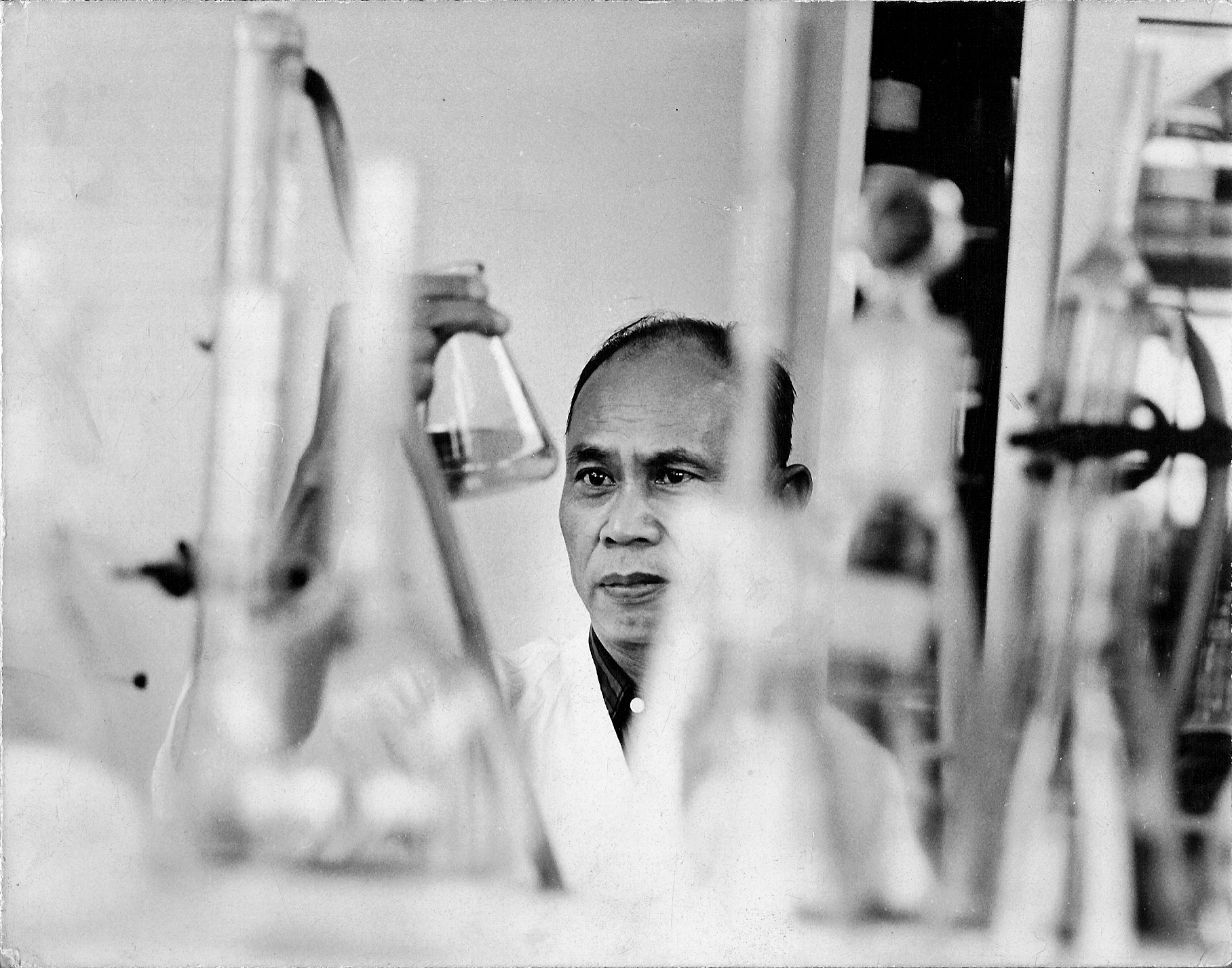

As it was, by reaching eighty-four he had more than exceeded the actuarial tables for a life begun in the middle of World War I as the pampered youngest of fourteen children of a former officer in China’s Imperial Army. An alumnus of both China’s top science school, Tsing Hua University in Beijing, and its elite secondary school, Nankai High School (which produced both Zhou En-lai and the recent Premier, Wen Zhiabao), my father became an expert in vegetable oil refining and one of the Chinese expatriates who developed and modernized the soybean industry in Brazil.

I try to imagine what kind of a centenarian he would have been: bed-ridden or active, muted or alert, paralyzed by a stroke (his worse fear), incoherent from dementia (my worse fear), or just a slower version of the father I had always known. At eighty, he had gone para-sailing at a beach resort in Thailand. The weekend before his death, he was still the designated driver on an outing to New York City with his circle of friends. The trajectory of these extra years could have gone either way. I think about this because, were he alive, I would want him able to answer the questions I now know to ask. Channeling Cheney’s Alice-In-Wonderlandesque’s words, I didn’t know then what I didn’t know, but now I know what I don’t know…

Top-most on the list would be the events that made the death of my mother, his wife of forty-one years when she had died nine years earlier than him, such an angry one. The metastised melanoma that shriveled her body to skin and bones within six months of diagnosis was easier to take than her bitter denunciations of him. Heard like an endless audio-loop during her last few weeks of life, they served to diminish my respect for both of them without increasing my knowledge about either. Sitting bed-side holding her hand during her last weeks, I cringed at the accusations she made, yet I could not leave, being both curious and a dutiful Chinese son. Her anger and focus robbed us of the conversations that would have made for a better closure for our own, oftentimes head-butting, relationship. I took my father’s forbearance and lack of response to the verbal pounding as natural under the circumstances: a person on their death-bed is allowed liberties accorded at no other time. I never imagined, as I have to come to discover, that I knew even less about my father than I thought.

A parent’s death removes the opportunity to clarify life-moments thought to be significant, if only because they survived into long-term memory. As fragments, their true meaning is speculative, the narrative broken in too many places. Yet, I carry them like a 19th-century furniture salesman’s sample-case: a stock of miniatures of the real thing for sharing with therapists and friends…

Here, a six year-old me – photo with my mother, in the backyard of our house in Uberaba, state of Minas Gerais in Brasil circa 1956-1957-  interrogated about a neighbor’s milk money missing from their porch, and brow-beaten into a false confession.

interrogated about a neighbor’s milk money missing from their porch, and brow-beaten into a false confession.

There, a frightened seven year-old rushed to spend the night at the same neighbor’s house across the street, because Mah-Mah was suddenly in bed for two days and a doctor had been summoned and he could see the lights on and Pah-Pah strobing past through the vertical window slats. (My later speculation is that she had had a miscarriage.)

Next, a twelve year old me wanting to go to the airport and see Pah-Pah off on a trip and having him say “No need to come to the airport: go play with Michael. I’ll be back in two weeks”…. and not seeing him again for two years and in another continent.

And there, almost fourteen, in that strange land, the midnight hour and angry voices behind their bedroom door and then Pah-Pah emerging, dark and wordless, to stand on the wooden landing outside the back stairs and stared at the night-sky for what seemed like hours…

My quest has always been to understand their motivation, the intentions and the rationale informing their actions. And yet, before the “why”, one must have the complete “what”. And therein is the seed for so much that has grown weed-like in my life: neither of my parents were good gardeners in that regard because, aside from the usual challenges of the multiple roles of normal adulthood – spouse, parent, worker – theirs carried a “difficulty multiplier”, like certain Olympic events. They were strangers – twice – in strange lands, Brazil and the United States. And that made their own up-bringing a useless blue-print for raising me, their only child.

I vowed to be different, to provide both stability and open communication with any child of mine. I took as role models the warm families around me – the Zamost clan and the Cohns in New Jersey, the Kundes and others in Brazil – and how they shared and communicated love. And when Julia was little, creating community with the families of her classmates from pre-school on, until they dispersed from St. Peter’s.

That’s not how I wanted it to be with Julia, my daughter, my “heart’s needle” (to steal from W.D. Snodgrass’s poem of the same name). I wanted her to know who I was, before being beyond able to answer questions. However harsh her judgement of my actions or the results, I wanted it to be based on good data, not speculation. I wanted her to understand her father for the most selfish of reasons: that however bungled and clumsily I may have played the role at times, the love driving the intentions was pure, fierce, and unconditional. It’s why the line from Othello’s last speech has so much resonance with me: “Speak of me as I am, nothing extenuate, or set down aught with malice”. My objective is not redemption or even forgivenesses: exposition and clarification would have been sufficient.

But now, as I am in twilight and find no way to open the subject except by a frontal assault that might result in a Pyrrhic victory, the rest of that line looms clearer and clearer: “Then must you speak of one who loved, not wisely, but too well.”

Lovely, Harrison. I know what you mean about parental mysteries. There are a few my own father left me that I’ll never unravel.